Going Green

Methane Reporting

[Methane] is Blowin’ in the Wind

Methane reporting standards for operators are tightening, increasing requirements for site-level detection and quantification.

By Wendy Laursen

More companies are moving to the flux method over dispersion modelling.

Image courtesy Daniel Franklin KrauseA growing share of oil and gas production is subject to methane abatement commitments, thanks to new participants in the Global Methane Pledge (e.g. Azerbaijan), the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter (e.g. PetroChina) and the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (e.g. the Nigerian National Petroleum Company).

The voluntary Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 is the flagship oil and gas reporting and mitigation program of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and now covers more than 42% of global oil and gas production.

Reporting advances from Level 1 through Level 5, with Level 4 reporting consisting of source level measurements and Level 5 consisting of two parts: site level measurements and reconciliation with the source level measurements from Level 4.

In April, responding to the continuous engagement with such schemes, Ipieca, the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP), the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) and the Energy Institute released an update of their “Recommended practices for methane detection and quantification technologies – upstream” as well as an online tool to help operators select and deploy methane detection and quantification technologies.

Image courtesy Ipieca

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ combination of technologies for methane emissions detection and quantification.”

- Lorena Perez,

Director for Climate and Energy, Ipieca

“Reporting standards for operators are tightening, increasing requirements for site-level detection and quantification technologies,” says Julien Perez, Managing Director, OGCI. “At the same time, technologies to detect and quantify methane emissions are rapidly evolving.”

The update includes six new technologies:

-

CI Systems: Metcam (a fully integrated, stationary quantifying optical gas imaging (OGI) device)

-

Exploration Robotics Technologies: Xplorobot Laser OGI (a handheld leak screening tool)

-

FLYLOGIX: fixed wing drones for offshore specific measurements

-

Net Zero Aerial: UAS Drone (a drone-based emission sensor)

-

Sierra Olympia Technologies: LWIR OGI Camera Core (an optical gas imaging camera)

-

University of Calgary: PoMELO (a truck-based measurement system)

Lorena Perez, Director for Climate and Energy at Ipieca, says there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ combination of technologies for methane emissions detection and quantification. Key challenges include technical applicability, certification, access and deployment, validation and performance as well as data management and security.

Environmental conditions are also important. Cloud cover can affect the reflected sunlight that passive sensors use to detect methane, snow cover can impact reflectivity, affecting some laser-based technologies, and high winds can disperse methane making it harder for sensors to detect methane plumes. These environmental conditions are also critical to conducting successful measurement campaigns.

Image courtesy OGCI

Technologies to detect and quantify methane emissions are rapidly evolving.”

- Julien Perez,

Managing Director, OGCI

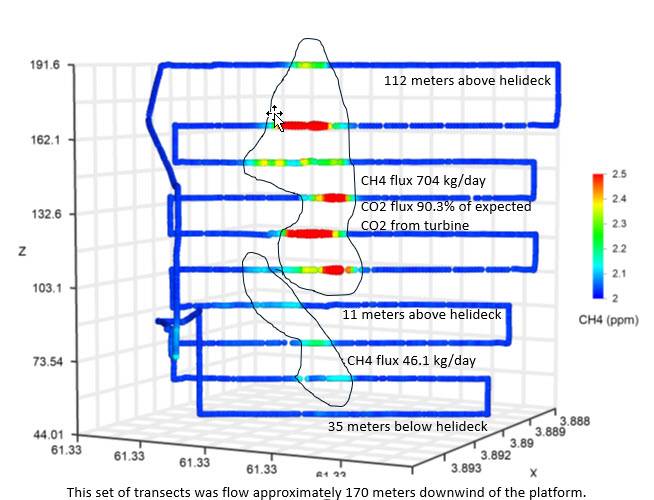

In January, SINTEF Research Engineer Daniel Franklin Krause released a technical memo summarizing the organization’s approach to quantifying offshore methane emissions in support of OGMP 2.0 Level 5 reporting. SINTEF has used the measurement strategy twice on Gjøa (reporting year 2023 and 2024) and for Cygnus A (reporting year 2023). “We expect to do these measurements on five different platforms in 2025 (three for Vår Energi in Norway, one for Ithaca Energy in the UK, and one for a joint innovation project (JIP) supported by five different oil companies in the UK),” says Krause. “The JIP is being conducted to arrive at a standard way of doing this for OEUK and will likely be used as an input for creating standards for IOGP. We are also in communication with other oil and gas companies in Australia and Brazil to help train their drone service providers with the approach we use.”

Methane emissions from offshore platforms can be divided into four groups: flare post combustion plume, gas turbine exhaust, the degassed component of produced water after it exits the discharge caisson below the water surface and cold‐vented and fugitive emissions. An FPSO or FSO will have additional methane emissions associated with the venting of tankers while crude oil and/or condensate is being loaded.

There’s two predominant numerical strategies for measuring these emissions: dispersion modelling which can be used to predict the downwind concentrations of methane by calculating how a known quantity of it would spread out in the air when released. Using inverse dispersion modelling, one can work backwards by using downwind concentrations to calculate a release rate. The issue with this is that the various assumptions involved typical result with increased error, as there can be numerous sources of emissions and various wind vortices.

The other strategy involves using the flux method which aims to measure how much methane is emitted per unit of time and involves measurements independent from the source activity, explains Krause. The flux measurements should occur sufficiently downwind of the platform to be outside of the wind wake and main wind vortices that form on the downwind side of the platform.

Image courtesy Daniel Franklin Krause

Early on, many drone service providers were flying way too close in the wind wake where you get a higher concentration of methane and using dispersion modelling did not work well.”

- Daniel Franklin Krause,

Research Engineer, SINTEF

More companies are moving to the flux method over dispersion modelling, he says, although there is quite a bit of variation in approach: different sensors with different detection levels and response times, flying transects at different distances and different approaches for measuring wind speed.

Both the windspeed and size of platform will affect how far the downwind wind wake will extend from the platform. Transects should largely bound the plume and allow for a re-creation of the general cross-sectional dimension of the plume. Flying these transects far enough downwind from the emission source will ensure they are outside of the wind wake so that a flux measurement can be made. As the plume is more diffuse, there will be more data points that can be measured in the plume. Flying too close means encountering the low pressure zone of the wind wake which will make it difficult to get enough measurements within the plume’s cross‐sectional area.

“Early on, many drone service providers were flying way too close in the wind wake where you get a higher concentration of methane and using dispersion modelling did not work well. Moving farther downwind (and outside of the wind wake) allows for a much better flux measurement,” says Krause. This, however, does involve using a methane sensor that can easily detect and quantify methane emissions as low as 10 to 20 ppb. For this, Krause uses the ABB HoverGuard methane sensor.

Next for Krause is making these measurements easier by developing an autonomous drone platform. This would enable making these measurements without having to send drone pilots offshore. He has also finishing a technical memo on conducting leak detection and repair (LDAR) surveys in compliance with the new EU methane regulation using ppb-level methane sensors. He is developing it in partnership with Offshore Norge. Krause is also working with his SINTEF colleagues to take VOCSim global, an in-house VOC simulation tool based on nearly 40 years of measuring VOC emissions (inclusive of methane) while tankers have been loaded with crude oil. Measuring and reducing these emissions has largely been limited to Norway, but now this tool can be used to understand these methane emissions much better for use with reporting in OGMP 2.0 globally.