An Engineering Life

Calvin Norton, Friede & Goldman

From Swamp Rigs to Floating Wind: Calvin Norton Reflects on 60 Years of Offshore Engineering

Calvin Norton spent 60 years with Friede & Goldman, with a career that spans and tracks some of the highest highs and lowest lows in the evolution of offshore energy production. As Norton retires and Friede & Goldman prepares to celebrate its own milestone anniversary, Offshore Engineer recently spent some time with Norton to document the projects, the technologies and the people that have evolved over the past six decades.

By Greg Trauthwein

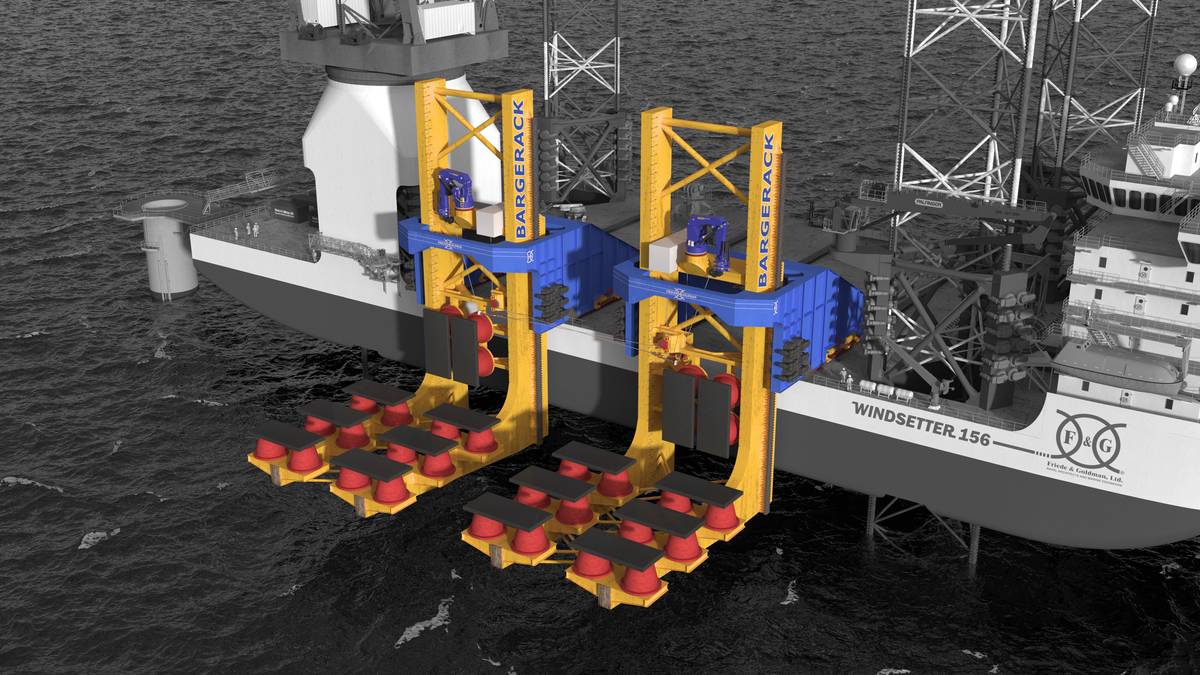

Friede & Goldman has evolved with the industry, and offshore wind has become a significant part of the mix. Despite the recent downturn of offshore wind in the U.S., F&G finds ample opportunities in the international market, including the DEME Innovation.

Image courtesy Friede & GoldmanWhen Calvin Norton joined Friede & Goldman in the early 1960s, the offshore industry was still in its adolescence. Floating drilling rigs were evolving, jack-ups were finding their legs — literally — and the Gulf of Mexico was the focal point of offshore activity. Over the next six decades, Norton would witness, and help shape, one of the most remarkable engineering evolutions in modern industrial history.

Now retired after 60 years with F&G — just shy of the company’s own 75-year anniversary—Norton sat down with Offshore Engineer to reflect on a career that bridged swamp rigs and semisubmersibles, deepwater challenges and digital tools, and a new frontier in offshore wind energy.

Beginnings in the Bayou

Calvin Norton’s maritime journey began in a small New Orleans-area shipyard building tugboats and barges. But it was a task involving the reactivation of a cold-stacked LST (Landing Ship Tank) turned tender-assisted rig that set his career on course.

“During the Coast Guard survey, it was found that the low-voltage cables didn’t meet new regulations,” Norton recalled. “I got the short straw and had to redesign the electrical system.”

It was during this project that a visiting engineer—who had helped build the original drilling equipment—mentored Norton on the intricacies of offshore systems. “That lit the fire,” he said. Not long after, Norton joined Friede & Goldman, where he would begin a legendary career in offshore rig design.

Designing for an Expanding Industry

One of Norton’s first major projects at F&G was the SEDCO 135 series of semisubmersibles, soon followed by the now-iconic Pace Setter designs of the 1970s. “Every job was different,” he said. “That’s what kept me in it for so long.”

A standout moment came in the early days of the Pace Setter project. A revision in ABS rules required a complete redesign of key connections in the bracing system — mid-build. Norton was dispatched to work directly with the shipyard team to ensure compliance without material waste.

“That project taught me the importance of thorough plan review and the value of being meticulous,” Norton said. “It was then I really developed my approach to structural plan checks, which I carried through the rest of my career.”

From semis to jack-ups — including the L780 series, Mod 2, Mod 5, and JU2000 variants—Norton’s work helped define the hardware of deepwater exploration for decades.

The Deepwater Revolution

“Back when I started, 600 feet was considered deep,” Norton noted. “Now it’s 12,000 ft.”

The push into deeper waters had a cascading effect on rig design, influencing everything from riser tensioning systems to mud circulation volumes, deck loads, and structural requirements. “It impacts everything the design team does—from structural engineering to naval architecture,” he said.

WATCH: F&G’s JU-2000E

Safety as a Design Imperative

When asked about the most significant advances in offshore safety, Norton pointed to both personal experience and systemic change.

“One of the pivotal moments for the industry came in the early ’60s with a gas explosion on a rig in the Gulf of Mexico,” he recalled. The accident was caused by a lack of gas detection systems plus the fact that the areas that processed the returning mud was not segregated from the rest of the rig … it was one big open area.

“That accident prompted the Coast Guard to mandate that mud processing be confined to isolated compartments — no longer open well decks.”

From Norton’s perspective, this was a particularly important accident and resultant rule making and engineering change as it was the beginning of the segregation of hazardous areas and inclusion of gas detection systems.

Norton also cited automation on the drill floor and innovations in BOP handling systems as transformative.

But perhaps most notable was the shift from slow hydraulic controls to the multiplex (MUX) electronic BOP systems. “Instead of relying on pilot hoses that slowed reaction time in deep water, MUX systems use electronic signals—effectively operating at the speed of light,” Norton explained. “It made operations safer, especially when needing to disconnect quickly.”

WATCH: F&G’s Windsetter 146 custom designed for Offshore Wind

Enduring Through Cycles

Having weathered six decades of boom-and-bust cycles, Norton emphasized the value of strategic downtime.

“During downturns, F&G used the time to develop new designs based on lessons learned from the last upcycle,” he said. “You reflect on the equipment placement, process improvements, and anticipate regulatory changes. That way, when the market picks back up, you're ready.”

His advice to young engineers entering the industry? “Learn every system. Understand how things connect and where improvements can be made. Those slow periods are your chance to grow and innovate.”

Offshore Wind: A Natural Transition

In recent years, Friede & Goldman has brought its decades of jack-up and semi-sub experience to bear on offshore wind development.

“Our history in jack-up design made us a perfect fit for WTIVs [Wind Turbine Installation Vessels],” Norton explained. “We understood leg design, spud cans, jacking systems—all critical to the new generation of wind support vessels.”

One of F&G’s notable contributions is the barge rack (bar-drag) system, which allows wind turbine components to be transferred at sea, minimizing port calls and optimizing installation time. “It’s about eliminating motion, increasing safety, and keeping the installation vessel focused on turbine work,” Norton said.

F&G has also been studying floating wind platforms—applying its expertise in semi-submersibles to address new geotechnical challenges where seabed installation isn’t feasible, such as seismic zones off the U.S. West Coast.

Looking Ahead: Fuels, AI, and Floating Solutions

As the offshore industry grapples with decarbonization mandates and efficiency pressures, Norton sees promise—but also challenges.

“Electrification of rigs has evolved from mechanical to SCR to variable frequency drives,” he said. “Going further—like connecting rigs to shore power—is complex. You’re dealing with long distances, high voltage, and safety concerns.”

While hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia are on the horizon, Norton believes internal combustion engines—albeit cleaner versions—will remain the backbone of offshore energy for the foreseeable future.

Nuclear power barges? “Maybe,” he said. “There are hurdles: safety, regulatory, and waste storage. And will ports allow them in? That’s a big question.”

Artificial intelligence and digital twins, however, are already proving their worth. “They’re improving predictive maintenance and efficiency,” Norton said. “Many OEMs now offer remote monitoring, which helps avoid failures before they happen.”

A Legacy of People and Ingenuity

As he steps back from full-time work, Norton is proud of the people he worked with at F&G. “It’s always been about solving problems—new or old,” he said. “We’ve had some of the most technically savvy people in the business, from structure to electrical.”

He’s also adamant that new designs must keep coming. “You can’t stand still. We’ve always tried to stay ahead of the competition with innovative solutions, and I think that spirit will continue.”

Despite retiring, Norton hasn’t gone far. “I still get emails and calls from the team,” he said with a smile. “I’m always happy to lend a hand. After 60 years, it’s like family.”