Markets

Offshore Wind in Poland & the Baltics

Poland and the Baltics are Joining the Race for Offshore Wind

European energy crisis increases appetite for offshore wind in countries dependent on Russian energy supplies

By Tomasz Laskowicz, Research Analyst, Intelatus Global Partners

In August 2022 in Marienborg (Denmark), representatives of the EU countries of the Baltic Sea region, announced a target of installing 20 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030.

An important role in achieving this target will be played by Poland, which intends to put 5.9 GW of wind farms into operation before 2030. Its footsteps are already being followed by the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which are preparing to announce auctions. By 2035, in Poland and the Baltic countries, the total value of installed wind farms is forecast to reach 30 GW, and capital expenditure is estimated at more than €60 billion. As a result of construction activities and operation and maintenance services through the long lifetime of the wind farms, the market will offer numerous development opportunities for the local and international offshore sector.

Till relatively recently, most of the European offshore wind development centered on the North Sea. The Baltic Sea has so far not been heavily explored for offshore wind energy development. Despite its relatively shallow depths and good wind conditions, there are currently only 9 wind farms operating in the Baltic Sea with a total capacity of 2.1 GW installed in Denmark, Germany and Sweden. The largest wind farm in operation in the Baltic Sea is the 605 MW Danish Kriegers Flak, commissioned in 2021. Currently there is one wind farm under construction in the German zone of the Baltic Sea and a further two preparing to move to the offshore construction phase.

Poland and the three Baltic states are seeking to meet the challenges faced by many European countries today: decarbonizing their economies and increasing energy security. The countries are currently under severe pressure due to rising energy costs, also in part resulting from the reduction of energy supplies from Russia. Following Russia's attack on Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic countries will accelerate the process of building energy independence based on renewable energy sources, including offshore wind.

395 GW of technical potential for offshore wind development

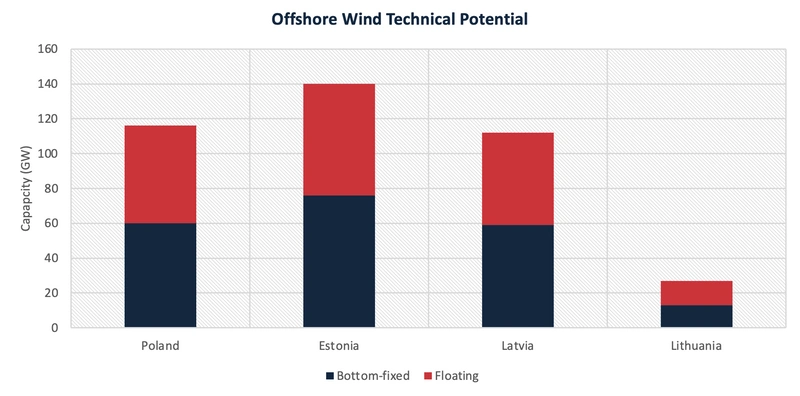

Poland and the Baltic States account for a technical capacity of 395 GW offshore wind, of which around 50% is suitable for bottom-fixed offshore wind farm development. Exhibit 1 shows that Estonia is home to the largest technical potential in the region although Poland and Latvia also share significant potential. Due to the available potential in shallow waters, it is logical to assume that for the foreseeable future most developments will be based on bottom fixed technologies. That said, certain local challenges related to soil conditions may result in non-traditional development solutions being deployed.

Exhibit 1 Offshore Wind Technical Potential

Concrete foundations in place

So far, Poland has enacted a special law to promote the development of offshore wind energy, under which projects have applied for a support scheme that awards guaranteed offtake prices. Support was granted in 2021 to 7 projects, which are currently at an advanced stage of obtaining environmental and construction permits and must be fully commissioned no later than 2028 in order not to lose support.

The projects in the first phase of support in Poland, are being developed by joint ventures, consisting of a local entity and an international partner experienced in the offshore industry. The total CAPEX for the construction of Polish projects in the first phase of support is forecast to be as high as €15.4 billion. Exhibit 2 shows that by 2035, CAPEX spending will be mostly concentrated in Poland and Estonia.

Exhibit 2 CAPEX by 2035 in Poland and the Baltic States

Leading players in the Polish market are state-owned companies, which are responsible for the largest project clusters together with their partners.

-

Polish Energy Group (PGE), together with the world’s largest offshore wind developer, Ørsted, has location permits for an estimated capacity of 3.44 GW to be developed in three phases.

-

Another cluster of three projects with a total capacity of 3 GW is being developed by privately owned Polenergia and Equinor.

-

State-owned PKN Orlen with Northland Power are developing a 1.2 GW project which appears to be at the furthest stage of advancement. A final investment decision has yet to be made, but the partners are at the stage of selecting preferred contractors.

-

There are a couple smaller projects included in the first phase of support, of 350-400 MW, developed by Ocean Winds and RWE.

At the end of 2021, the Polish government identified 11 new locations for offshore wind energy development and the criteria for evaluating applications. Approximately 130 applications have been submitted for 11 new sites. The allocation of 11 new sites, which will further accelerate the Polish offshore wind industry, is expected in late 2022/2023. The total installed capacity at the designated 11 new sites could amount to 9.3 GW. The legal framework also provides for the launch of auctions in 2025 and 2027, where energy from wind farms with a total capacity of 2,500 MW will be contracted.

Lithuania has so far announced two auctions for farms of 700 MW each, with the first announced for the second half of 2023. Construction is planned in the second half of the decade.

Latvia and Estonia a planning to develop a joint 1 GW wind farm towards the end of the decade. A pre-feasibility study is currently underway to propose the best location.

Estonia, which wants to generate electricity from 100% renewable energy by 2030, has the technical potential to develop up to 140 GW of offshore wind. Estonia plans to develop projects in three clusters: in the Gulf of Riga and in the vicinity of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa islands. Over the past few years, more than 30 applications have been submitted to the Estonian authorities for permits for offshore wind projects, with several applications for the same location. An auction process has recently been announced. Large projects up to 6 GW are being planned for Estonia and interested developers include some of the world’s largest offshore wind firms.

It will certainly be difficult to fully utilize the technical potential due to possible spatial conflicts hindering the development of offshore wind farms. The generally include restrictions related to areas excluded due to defense activities, shipping routes, opposition from the tourism sector, fisheries, or the coal-based energy sector. A further challenge may be the availability of supply chain and infrastructure facilities, including installation vessels and crews, due to the rapidly growing ambitions for offshore wind development worldwide.

Capital spots opportunity in offshore wind supply chain

Growing demand for offshore wind services and products is a driver for the development of a domestic supply chain, especially in the provision of maintenance and operations services, which, according to an analysis by Intelatus Global Partners, is forecast at around €605 million per year before 2030 in Poland alone, and will grow to €1.8 billion per year by 2035. A long-term demand of around 20 CTVs based at local service ports is forecast to be required just to service the 7 Polish projects scheduled to come online by 2030.

Projects in Poland and the Baltic states will be designed with large-scale turbines, reaching 15 MW or more. Given the forecast increase in regional and global offshore wind activity at the same time, this means that there will be increased competition for a limited pool of material and service suppliers. The dynamic development of offshore wind power in the Southeast Baltic region will require securing the supply of components based on a global supply chain but will also create opportunities for order fulfillment based on local technical facilities. As an example of local supply chain investment, a €100 million wind turbine tower factory will be built in Gdansk, Poland. A further example of local supply chain development is the Estonian Port of Tallin. In order to adapt infrastructure to the construction and maintenance of offshore wind farms in the Baltic Sea region, the Estonian Port has announced an investment of up to €53 million to build a new quay with dedicated storage area.

Poland and the Baltic countries do not currently have existing offshore wind farms, but there is a developed offshore and marine industrial capability in these countries including shipbuilding, which will certainly be interested in participating in the supply chain. The local supply chain in the past has supplied wind farm components. Going forward, components that can be supplied locally also include cables, power equipment, steel products and others. The coming months are likely to bring new advances in offshore wind energy development, which will permanently change the structure of the energy mix of Poland and the Baltic countries.

For more information about the Intelatus Global Partners U.S. Offshore Wind Report, please visit www.intelatus.com or contact Michael Kozlowski at +1 561-733-2477 or Philip Lewis at +44 203-966-2492

About the Author:

Tomasz Laskowicz is Research Analyst at Intelatus Global Partners. He is a PhD candidate at the doctoral School of Social Economic Sciences at the University of Gdansk.