It’s going to get harder to hide

Submarine locations are highly protected assets. The location of endangered marine species might be a desirable secret to keep too, and so might commercial sensitive subsea energy data. But it’s going to get harder to hide with new developments in subsea communication.

By Wendy Laursen

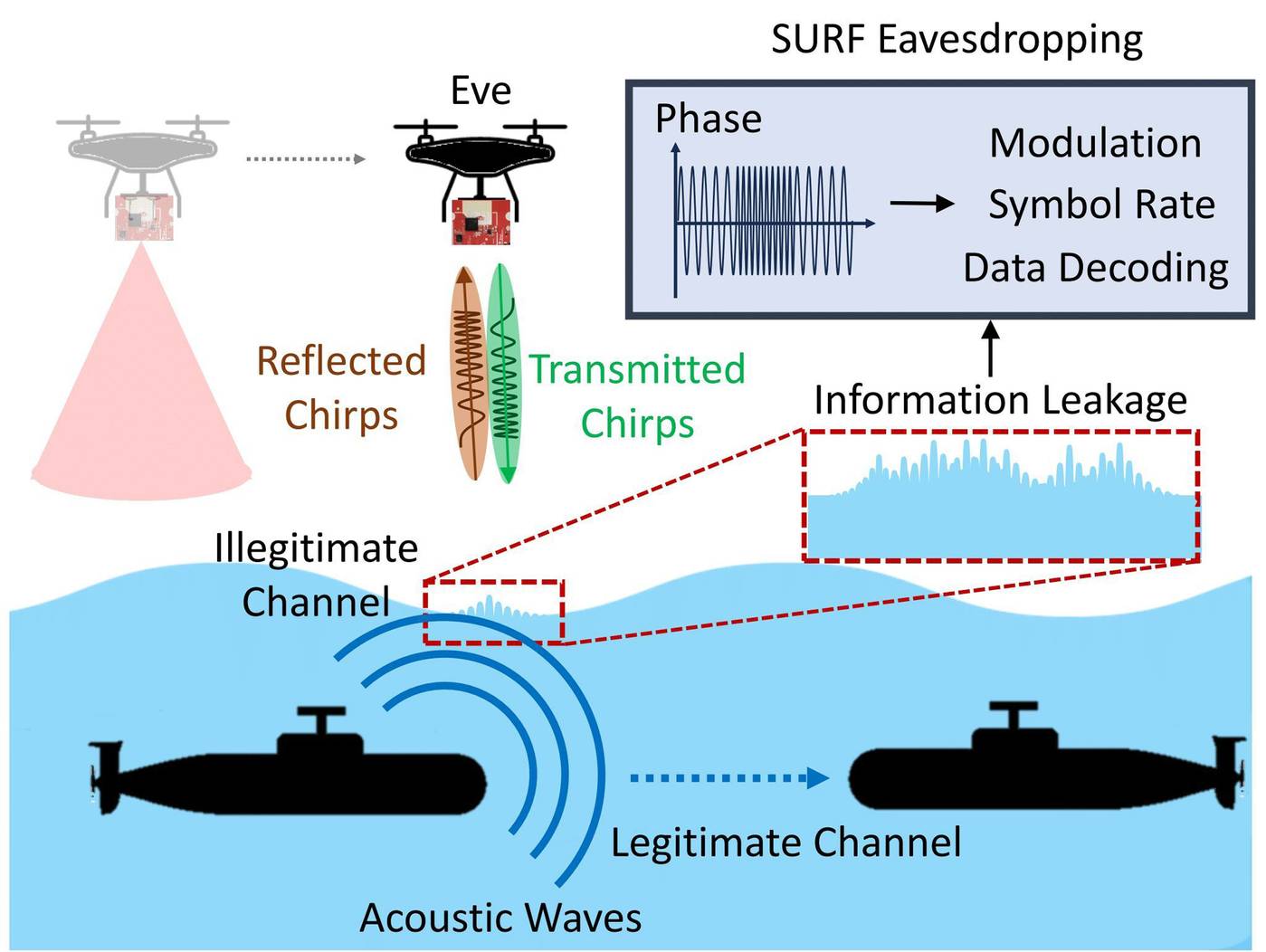

The security of underwater communications relies heavily on the inability of sound traveling underwater to penetrate the surface because of the acoustic impedance mismatch between water and air.

Conventional systems for cross-medium eavesdropping require deploying passive sonobuoys on the water surface to listen to messages underwater using hydrophones. More recently meta-material patches that can amplify underwater vibrations can do it too, and they can enable the signals to be picked up by a remote airborne receiver.

The challenge with these approaches also have a limited coverage area for detecting underwater signals compared to drones which can fly over and scan wider areas of the surface, says Dr. Fadel Adib of MIT.

In 2018, Adib’s MIT group realized that underwater sound waves create tiny vibrations on the water’s surface. His team used a radar system mounted on a drone to read these vibrations in real time and then decode the signal and extract the message being sent.

The device can detect vibrations, only microns in scale, and perform a beam search (using antenna array beamforming) to identify the location on the surface that has the highest vibration and is therefore closest to the source of the acoustic signals.

The system works even if the drone is not directly above the source, and the deeper the source, the broader the beam of vibrations is going to be that reaches the surface. And it works despite naturally occurring surface waves often 4-5 orders of magnitude higher than the vibrations being detected and decoded.

The technique relied on cooperation between the air and sea parties — sharing data rates, frequencies and other key technical details in advance. Now, however, collaborating with Dr. Yasaman Ghasempour and her Princeton University team, they have developed a way to decipher messages without knowing any of the technical details.

The Princeton team developed new algorithms that capitalize on the differences between radar and sonar to uncover the physical parameters needed for decoding without cooperation from the underwater transmitter.

Although the researchers are using commercial radar systems to detect the vibrations, Adib believes it is theoretically possible to do the same thing from satellites. “What it really depends on is the power that you're transmitting. We were working with a lot of commercial, off-the-shelf radars, but if you look at military satellites, for example, they have much more powerful capabilities, so they'd be able to pick up the signal from much higher, depending on the signal to noise ratio.”

Deploying this technique in real-world naval scenarios still presents challenges that remain unresolved. Among these are the mobility of underwater nodes that can cause Doppler shifts in the transmitted data, complicating the demodulation process, large natural waves in the ocean and the need to accommodate increased data rates.

Although encryption could potentially complicate the process too, it is often challenging to implement in power-constrained devices, particularly in underwater environments, says Adib. Asymmetric encryption requires significant computational power, leading to high energy consumption which is unsuitable for the resource-limited devices commonly used in underwater environments.

It was thinking about power considerations the led Adib and his team to develop a new underwater communication technique. “Backscatter is a completely different form of underwater communication that we invented and we've been developing. Backscatter modems communicate by reflecting rather than transmitting sound. Let's say that you have a remote projector or a transmitter, or even a whale, the modem is almost like a mirror, so it's reflecting the sound and it's encoding the reflections. And if you look at changes in these reflections underwater, you'd be able to pick them up using a hydrophone and decode the signal.”

Backscatter modems consume about a million times less than traditional underwater modems. This means they can be deployed for a very long time.

“Backscatter systems can be deployed at scale. Even if each of the sensors is not very powerful, combined, because you can deploy them at scale, you get even better information,” says Adib. “And they are much cheaper than sonobuoys.

The new modems could be used to detect sound or images from, for example, submarines or endangered species. “Backscatter is a method for detecting submarines in a completely passive way, to the extent that it does not even need to transmit the signal for you to be able to detect it, because you detect it based on the reflection of the signal from the dark scatter node.”

Adib is developing the concept so it can be used to enable underwater robots to localize and navigate, particularly in shallow waters that are usually challenging for acoustic beacons using long baseline (LBL), SBL, and USBL technology. In these systems, an acoustic transceiver on the underwater drones leverages deployed beacons for localization.

Existing approaches do not meet the accuracy, power budget or cost requirements of compact underwater drones, Adib says. “In terms of accuracy, most of these systems achieve tens or hundreds of meters of location accuracy, which is suitable for the open ocean but not for narrow waterways or coastal environments.”

His solution, 3D-BLUE, integrates backscatter nodes into the underwater robot and uses them for localizing it by leveraging the physical properties of the backscatter technology to efficiently extract spatio-temporal-spectral features from the backscatter signal.

“We have implemented an end-to-end prototype of 3D-BLUE on a Blue Robotics BlueROV2 robot and custom built a backscatter localization system. Our results demonstrate that 3D-BLUE can localize the robot with an accuracy of around 0.25 meters at close range and an accuracy of around 1.4 meters at a range of 10 meters. This high localization accuracy opens important commercial naval, and environmental applications in challenging shallow-water environments.”

In the future, Adib is looking to apply the concept to longer ranges using more sophisticated backscatter designs, explore sensor fusion (acoustic-visual) methods, develop advanced signal processing techniques to deal with Doppler shifts at higher speeds and integrate the technology on swarms of micro-robots where its ultra-low-power would be even more advantageous.