Market

Dredging

Dredging: Important Developments Will Impact Business

The dredging market is undoubtedly challenging, but there’s real cause for optimism as large and impactful opportunities come knocking.

By Tom Ewing

For dredging company officials, the first quarter of 2021 was a pretty good start to a new year. In a tough business, challenges and pitfalls are always expected. But from a bigger picture perspective—markets, regulations and policies—company officials couldn’t be faulted if a bit of optimism infused their worldview.

There are a number of reasons for this. Many are well known and don’t need to be detailed here. Just quickly, though, WRDA 2020 would be at the top of the list. WRDA, passed last December, provides new funding and policies that will expand dredging opportunities.

Just as important, dredging companies are ready to rock-and-roll with new equipment. At Callan Marine, for example, the General Bradley is a new 341-foot, 28-inch cutter suction dredge (CSD) to be deployed in 2021. Callan’s big 32-inch General MacArthur entered service in 2020.

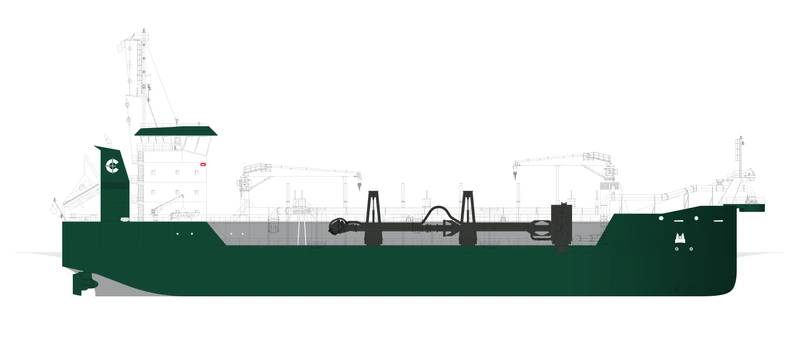

Still to come, Weeks Marine expects delivery in 2023 of a 6,540 cubic meter trailing suction hopper dredge (TSHD). Manson Construction awaits, also due in 2023, a 15,000 cubic yard dredge that’s 420 feet long and 81 feet wide. And Cashman Dredging and Marine Contracting Co., LLC recently signed a design contract with IHC America Inc. for a new 6,500 cubic yard TSHD expected to enter service in 2024.

Cashman Marine’s new hopper dredge is expected to enter service in 2024

Additionally, companies see new markets, particularly offshore wind which got a big boost at the end of March when President Biden presented a national goal to develop 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030. DOE Secretary Granholm said this effort would include $3 billion in new energy funding, expected to leverage $12 billion annually in direct investments.

Great Lakes Dock & Dredge (GLDD) is one company with its eye on these developments. GLDD is designing a rock installation vessel that will be used to anchor turbine foundations. Lasse Petterson, GLDD president and CEO, told Marine News in January that the new equipment “addresses specific needs in the growing offshore wind market.”

Also significant among these capital investments is GLDD’s investment in personnel. In January, the company named Eleni Beyko as senior vice president offshore wind. A naval architect and engineer, Beyko’s background includes managing the Makani wind-borne energy spar offshore platform installation in partnership with Shell and Google X.

For dredgers, Bill Hanson, GLDD’s senior vice president of government relations, cites two new challenges with offshore wind. One, projects will be in the open ocean and, second, in deep water, at depths greater than most coastal projects. “We anticipate complicated dredging for cables and other parts of the installations,” Hanson said. Investments in new, highly automated equipment will take on these challenges. “This will increase our efficiency,” Hanson explained, “and with accuracies that are re-ally impressive when you consider the scope of the work being done.”

Richard Balzano is CEO and executive director of the Dredging Contractors of America (DCA), starting that position in December 2020. Balzano’s maritime career includes U.S. Navy service and Deputy MARAD Administrator.

As he looks ahead, Balzano foresees an increased number of projects moving through USACE’s contracting process. Balzano says that WRDA’s impact, as well as supportive moves from the Biden Administration, e.g., a recent EO that strengthens “Buy American” provisions, will help the industry “grow capacity and continue investments in newer and more efficient equipment.”

Balzano said dredging companies are watching to see how the process of new business develops. DCA seeks an expansion that will be efficient in awarding work and builds on industry’s capabilities. Project scheduling and the need to stay aligned with seasonal, environmental or safety factors are top concerns.

“I would say that scheduling is one of the foremost issues facing our industry,” Balzano explained. “There are a lot of demand signals that have to be coordinated and deconflicted to help maximize our industry’s capacity.”

The Corps’ harbors and waterways project list will expand as increased Harbor Trust Fund monies become available. The project selection process will be important, as will project scope, i.e., minimal efforts or full completion. These decisional issues were raised in a 2017 GAO report on inland harbors and dredging. GAO’s concern then was that the Corps’ analytical tools fell short in evaluating comparative benefits across a range of project options.

GAO recommended the Corp assess its existing tools and capabilities when allocating funds from the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund. These are still open, unresolved concerns at GAO.

Scheduling and coordination are also common concerns in discussions about “beneficial use” (BU).

Again, referencing WRDA 2020, Congress expanded demands for BU, establishing a “National Policy on the Beneficial Use of Dredged Material.” WRDA expands BU demonstration projects from 20 to 35. Additionally, it requires Corps District Commanders to develop—within one year, less than eight months as this report is written—five-year regional dredged material management plans which need to include BU evaluations and goals.

BU is not easily done. Demonstration projects have moved slowly or haven’t started. In December 2018, for example, the Corps selected ten demo beneficial use projects. In a June 2020 update report to Congress, just three were finished.

Beneficial use has many inherent challenges: demand, supply, timing, transport, contamination, to name just a few. Plus, officials who need sediment frequently aren’t aware of available supplies. The reverse is true for dredgers who may be aware that certain material has value but unaware of who needs it, and when.

Inertia is also a challenge; we’ve always dumped in the bay or the ocean. We keep dumping in the bay or the ocean.

Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

New ideas

In San Francisco a coalition of groups working on Bay restoration projects has developed an online tool called SediMatch, which functions as a material exchange. SediMatch seeks to make beneficial use a business-as-usual practice instead of an exemplary anomaly (one of the still unfunded 2018 demo projects is in the San Fran-cisco Bay area).

SediMatch is a collaborative program of the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture (SFBJV), the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), the San Francisco Estuary Partnership (SFEP), and other groups. A central goal was developing an easily accessible database matching sediment needs with surplus sediment—the critical in-puts to make beneficial use succeed.

Briefly, it’s important to recall some of the information required within WRDA 2020’s five-year plans: identifying reuse projects and estimating capacity; beneficial use goals; and project descriptions identified through stakeholder solicitation and coordination.

SediMatch presents all of this information. Data is within an Excel spreadsheet and it is extensive, providing, for example, contact information, material quantities, availability and transport information.

Again, SediMatch is only focused on San Francisco Bay. It’s underlying concepts, though, are likely applicable in any region with dredging and reuse goals.

In an interview, Brenda Goeden, Sediment Program Manager with the San Francisco Bay Development Commission, explained that a regional San Francisco goal is to maximize best use of 40% of dredged material, in wetlands, for example, or flood control or recreation projects or as foundational material, as appropriate, for bike paths and roads.

Dumping sediment into the ocean or Bay is relatively cheap, Goeden said, just requiring time and travel costs to a dump site. Dumping, however, presents its own environ-mental and ecological issues and frequently faces strong opposition.

Goeden sets BU policies in a broad context. First, she notes that multiple projects in the Bay area require sediment, again, for wetland restoration or flood control. Then, she notes the Army Corps’ three central missions: navigation, ecological restoration and flood protection. “With BU,” she says, “the Corps can deliver on all three missions with one scoop. That would be a real big change.”

Expanded coordination across federal agencies would be especially helpful. For example, an Army Corps navigation project will produce sediment. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service project frequently needs sediment for habitat for wetland and fish species, also beneficial to NOAA. The Department of Interior frequently needs sediment for parks or recreation purposes.

The point is, Goeden emphasizes, a more holistic approach among agencies could lead to different decisions. It may not make sense for the Corps to pay to send barges 55 miles to San Francisco’s closest dumping site when managers at other federal Bay projects need sediment. (A 2019 Congressional Research Service report lists San Francisco with the most expensive unit cost for dredging in the country: $24.27 per cubic yard. New York is next: $23.17. Cheapest is New Orleans: $2.62.)

For beneficial use, operational changes are a challenge. Federal regulatory inertia can keep existing practices in place. Goeden references the “federal standard” which looks only at least cost and environmentally acceptable vs. environmentally beneficial or even preferred.

Goeden expressed optimism though about new directions. After all, federal agencies are active partners within the Bay’s restoration efforts. And she thinks that WRDA 2020 will begin to push dredging and beneficial use into greater alignment. She cites as helpful WRDA’s Section 125 which references nature based benefits when considering a federal standard. Another change that’s needed: Private sector companies need to become more active in the SediMatch database.

SediMatch’s opening page presents two critical numbers: 693,205 cubic yards total sediment available and 33,401,125 cubic yards wanted in total. That’s over 10 years.

There should be enough time to make some changes.